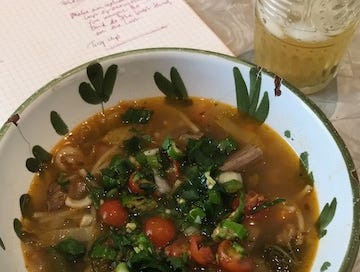

I made a little soup this week. Sautéed some onion and backyard garlic in a nice glug of olive oil. Added diced potato and carrot, salt, water to cover. Let them simmer until they were getting soft, then added local green beans, not mine, mine didn’t come in this year, but nice local green beans, cut into soup-spoon lengths. Let them cook until they were done. No crunchy green beans for me. Then some orzo added at the end. No stock, a splash of fish sauce was all it needed. Topped with the first few garden tomatoes, some basil, a little more olive oil, some parmesan. A piece of bread. Lunch.

Soup seemed to steady the existential wobble of these past weeks. Weeks when day after day temperatures have been in the 90s, pushing 100. Weeks when the sky has been white with wildfire smoke. We haven’t seen blue skies since June. However, it’s good to know that even when it’s apocalyptic outside, I can rustle up a delicious meal out of things that are in my house and garden. Which was, after all, one of the cornerstones of the project I started in this house all those years ago.

It’s what I do when I don’t know what to do. I make something. Often in the kitchen.

I learned to cook in the wake of my parents' divorce. We moved to Madison when I was just starting 7th grade, to a condo in a development full of divorced moms and latchkey kids. After a couple of false starts, my mother, who never expected to have to work, found a job as a travel agent. So we’d come home from school, and would be on our own for a couple of hours. After a while, she started teaching me to get dinner started over the phone. I’d slice onions and put a pot roast in the covered aluminum roaster (that I still have, and still use for this) with a can of tomatoes, a can of beef broth, and a packet of French onion soup mix. How did we not die from the salt? In the oven it would go, and we’d head back out to play various strange and competitive kid games in the cul-de-sac. Dad was not great about paying the child support, so there was a lot of scrimping.

Groceries were always someplace my mother figured we could stretch the money. Pot roasts from cuts Mom wasn’t familiar with, but that were big, and cheap. Pot roast, then sandwiches, then pasta, then soup — same with turkey. There was a lot of turkey on an out-of-season frozen Butterball for three people. Same cadence: roast, then sandwiches, then on pasta, then soup. When I turned sixteen, she handed me the car keys, the list, and a signed check. “Don’t spend more than fifty dollars,” she’d say. Later I spent two years broke in New York City, working for a cookbook packager — I had no money at all after rent and bills, but I had access to a big cookbook library. So I started reading up on cucina povera. How to stretch a dollar and also eat really well? It was New York, so I had the tiny shop down 2nd Avenue that only sold fresh mozzarella and olives, the Union Square Farmer’s Market when it was just getting off the ground, and there were still bakeries, and butcher shops and fish mongers. I remember asking a fishmonger what to do with a mackerel, because it was so beautiful and so cheap.

When people complained about cooking every night during the pandemic, my first grumpy thought was “well we cooked dinner every night when I grew up and no one complained,” and then I remembered the housekeepers and the country clubs. I grew up in a wealthy suburb where most families had housekeepers. They'd feed the little kids in the kitchen before they left for the night, leave something that could be heated up later for the parents and the big kids. I remember a world where families didn't eat out like they do now, but we had country clubs, where you were obligated to pay a certain amount for the restaurant every month whether you ate there or not. So that's where people took kids, or ate out on a Tuesday night. When we were little, before the bankruptcy, we ate at the club after tennis or swimming most of the summer. When people do that nostalgic thing about “your grandmother’s cooking” — oh boy. Mine did not cook. Neither did her mother. When my great-grandparents money ran out at the end, and people couldn’t afford house servants, my great-grandmother refused to learn to cook. So my very proper great-grandfather learned.

Alicia Kennedy and I got chatting on Twitter this week about food media. I was bemoaning the way the focus shifted, sometime around the launch of Lucky Peach, from home cooking to celebrity chef and restaurant cooking. There’s a whole generation (or maybe two?) behind me who didn’t grow up cooking. Who either microwaved something frozen, or ordered takeout, or went out as a matter of course. Now there’s services like DoorDash (although not here in Livingston) and UberEats as well. There's a whole cohort of younger folks who seem to equate “cooking” with the performative cooking of TV food shows and restaurants. Even my old standby, “The Splendid Table”, no longer has the call-in feature where folks ask what to do with a tree’s worth of apricots, or how to cook with some ingredient they found on their travels. Francis Lam sounds like a lovely guy, but his background is cookbooks, which are currently centered around chefs and restaurants.

Because making something from what I have has always been the place I turn to when I’m feeling as existentially wobbly as I have these past weeks of hot wind and smoky skies, I pulled out the Elizabeth Luard cookbooks again. I discovered her during pandemic. I can’t remember how? But I found her via her memoir Family Life, and then her two big cookbooks, European Peasant Cookery, and The Old World Kitchen. Luard grew up wealthy but her father died in WW2, and her stepfather came to dislike her and her brother, as if they were cuckoos in the nest of his own children. She married a charming bounder, and found herself with four kids, living in Spain, with almost no money at all. She learned to feed them all from her housekeeper, and became fascinated by traditional peasant cooking even as she could see it disappearing around her. This is not showy cooking. This is not television cooking, or the hottest restaurant, or even a food truck popup. This is the cooking of making something delicious from what you have. In a single pot, over one heat source ... because heat is money. The cooking of going out into the garden or to the local market, and seeing what is ready this week. Here, it’s been unseasonably hot and dry after a spring that was characterized by several very late frosts. I’ve been watering, but my garden is only now beginning to produce — and in tiny quantities. A few cherry tomatoes. The first skinny zucchini. Chard at last. Peppers and parsley. That’s about it. Luckily, our local Hutterite colonies are showing up with lovely onions and carrots and green beans and pickling cucumbers. And a family that ran roadside stands in the Boston area for decades retired here, built a greenhouse, and opened a stand for us.

And so, as it was all coming off the rails, I went into the kitchen to rustle up a soup. A simple soup made from local stuff I had on hand. A soup that didn’t have a recipe. A soup I’ve made a million times, in a million different ways. A soup that has saved me more than once over the years.

Sometimes cooking is just cooking. It’s what you do to feed yourself and your loved ones. And it’s what you do over, and over, and over again. Because you can. Because you are still here, even if under skies of smoke, and a hot wind. We’re all still here, and people need something good to eat, something that will feed their souls. For me, that’s always soup.